After leaving the Old Naas Travelling Stock Route on Wednesday, 29th October 2025, Marija and I headed to the former Orroral tracking station. Andrew VK1AD had recommended that we visit the site, and we are very pleased that he did, as we found it extremely interesting.

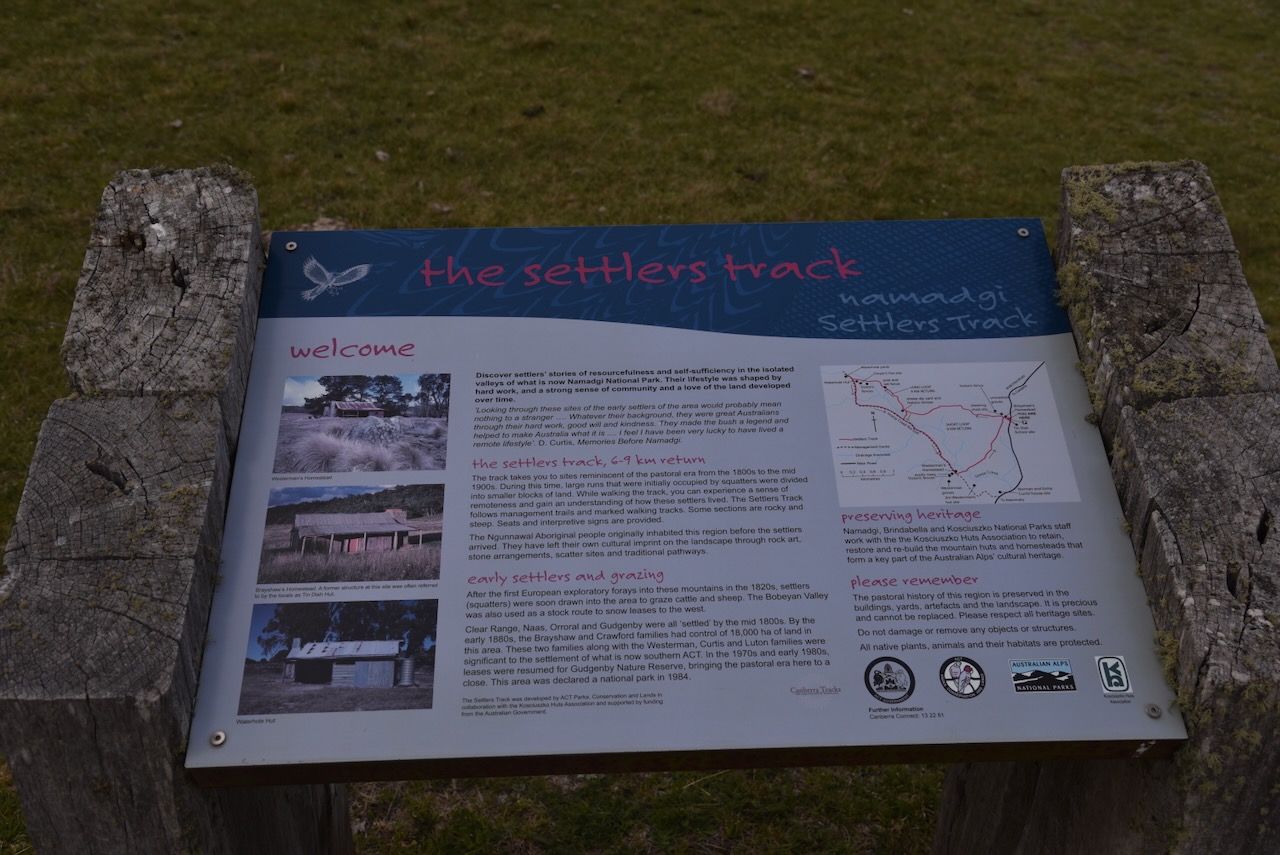

To get there from Old Naas, we headed south on Boboyan Road and then took Orroral Road. We first crossed the Gudgenby River and then into the Namadgi National Park past the Orroral campground. A little further along, we came into the Orroral Valley, with a cleared area and Orroral River on one side of the road, and thick scrub of Namadgi on the other.

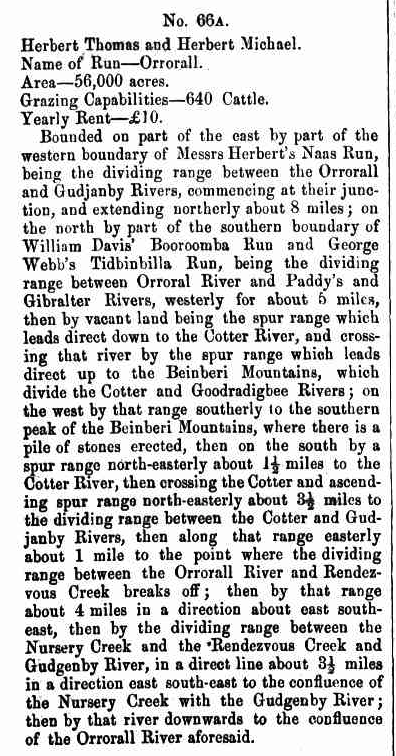

The Orroral Valley is believed to take its name from the Aboriginal word Urongal, meaning tomorrow. Urongal was depicted on the 1834 map by the explorer Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell. In 1839, Land Commissioner Bingham referred to the area as Orrooral. In 1847, the area was referred to as Ararel in the NSW Government Gazette. In 1856, it was referred to as Orrorall in the NSW Government Gazette. In 1865, it was referred to as Orrorall in Fussell’s Squatting Directory. In 1867, it was referred to as Oralla in Bailliere’s Post Office Directory. (ACT Heritage Council 2016) (NPA 1992)

The first European in the area is believed to be William Herbert. I spoke a bit about Herbert in my Old Naas post. Herbert was transported to Australia for life in 1816. He was initially a squatter and was then granted land on a leasehold basis. Several other people owned the run up until 1864. (NPA 1992)

Above: Item from the NSW Govt Gazette, Wed 24 Dec 1856. Image c/o Trove

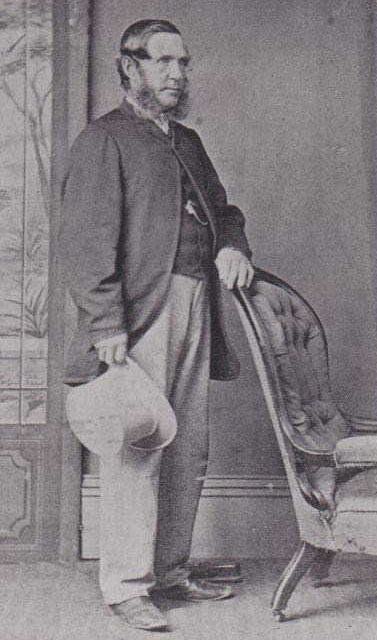

In 1864, the property was transferred to Charles McKeahnie. He was born in October 1809 in Argyll, Scotland. He was a bounty emigrant who arrived in Port Jackson in 1838 with his wife Elizabeth and their baby daughter Ann, aboard the ship St George. McKeahnie died in April 1903 at Queanbeyan, NSW. (ancestry 2016) (NPA 1992)

Above: Charles McKeahnie. Image c/o ancestry.com.au

In 1911, the Orroral property was sold to Albert Bootes from Gundagai. Albert George William Bootes was born in 1888 in Burwood, NSW. He ran the property whilst residing at Gundagai and in 1923 came to the district to reside permanently following his purchase of the Bywong property. In 1927, he purchased property at Gudgenby. Bootes died in June 1963 in Queanbeyan, NSW. (ancestry 2016) (NLA.gov.au 2026) (NPA 1992)

Above: Albert Bootes. Image c/o ancestry.com.au

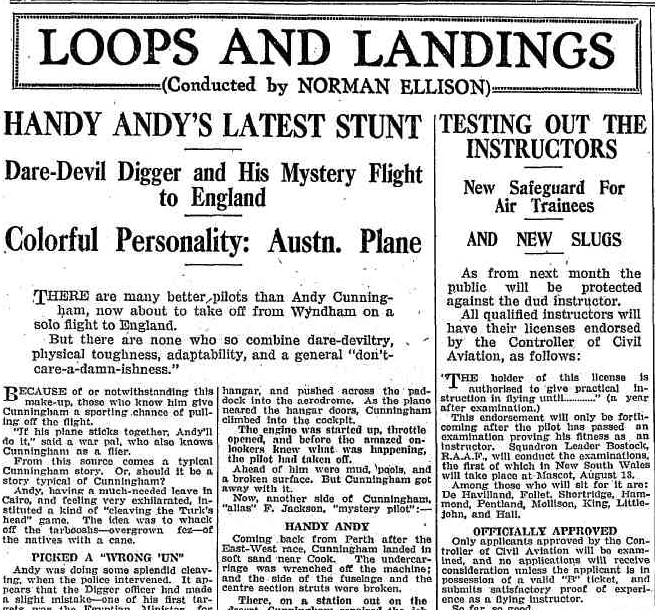

In 1926, the property was sold to Andrew Twynam Cunningham. He was born in September 1891 in Tuggeranong, ACT. (ancestry 2016) (NPA 1992)

Above: Andrew Twynam Cunningham. Image c/o ancestry.com.au

Cunningham fought at Gallipoli with the 1st Light Horse Regiment. where he was wounded in 1915. He then became a Lieutenant with the 2nd Light Horse Brigade and, in 1917, was promoted to Captain and led the 2nd Machine Gun Squadron. He was awarded the Military Cross in June 1917 and was mentioned in Despatches in July 1917. Cunningham became known as a daring pilot with his De Havilland Moth biplane that was known as the Orroal Dingo. His landing strip was located between the homestead and the Orroral River. (ACT Memorial 2024) (ancestry 2016)

Above: Cunningham’s aircraft VH-UOF. Image c/o Referee, Sydney, Wed 6 Aug 1930. Image c/o Trove

In 1930, the Referee Sydney stated the following about Cunningham: ‘there are none to combine dare-deviltry, physical toughness, adaptability, and a general don’t care-a-dam-ishness’.

Above: part of an article from the Referee, Sydney, Wed 6 Aug 1930. Image c/o Trove

Cunningham built the Orroral woolshed in 1930. Cunningham died in August 1959 at Randwick, NSW. (ACT Memorial 2024) (ancestry 2016) (NPA 1992)

Marija and I were keen to visit the Orroral homestead and woolshed, but it appeared that access was not allowed, so sadly, we kept heading on our way. It was slow going along the road due to the wildlife.

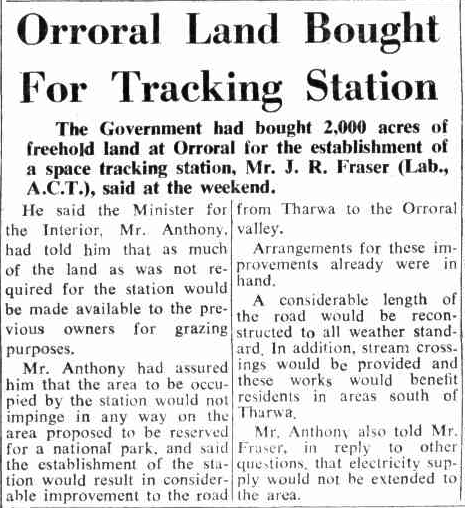

Not far past the homestead, we reached the former Orroral Tracking Station, which was one of three tracking stations established in the sheltered valleys of the Australian Capital Territory as part of NASA’s worldwide tracking and data network.

In 1964, the Australian Government purchased 2,000 acres of freehold land at Orroral for the establishment of the station.

Above: article from The Canberra Times, Mon 13 Apr 1964. Image c/o Trove

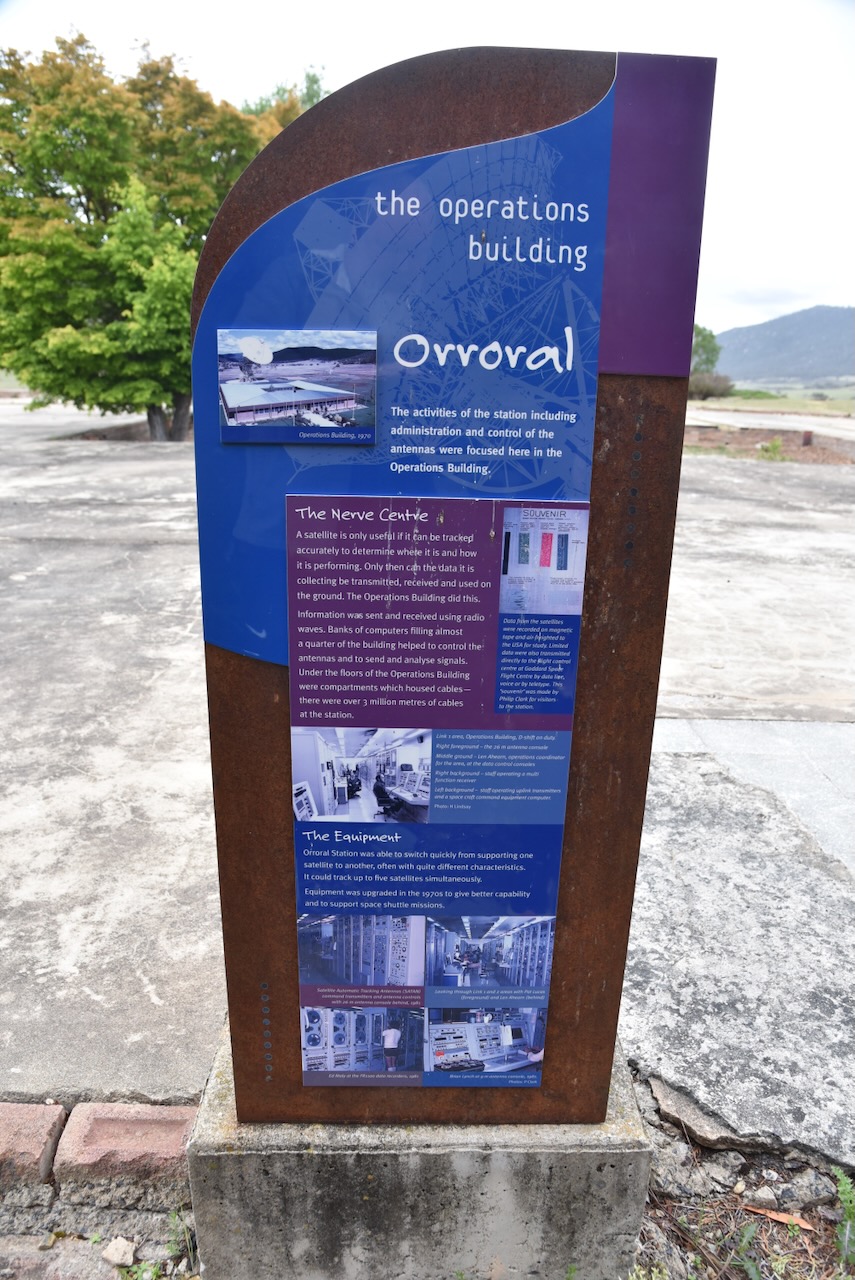

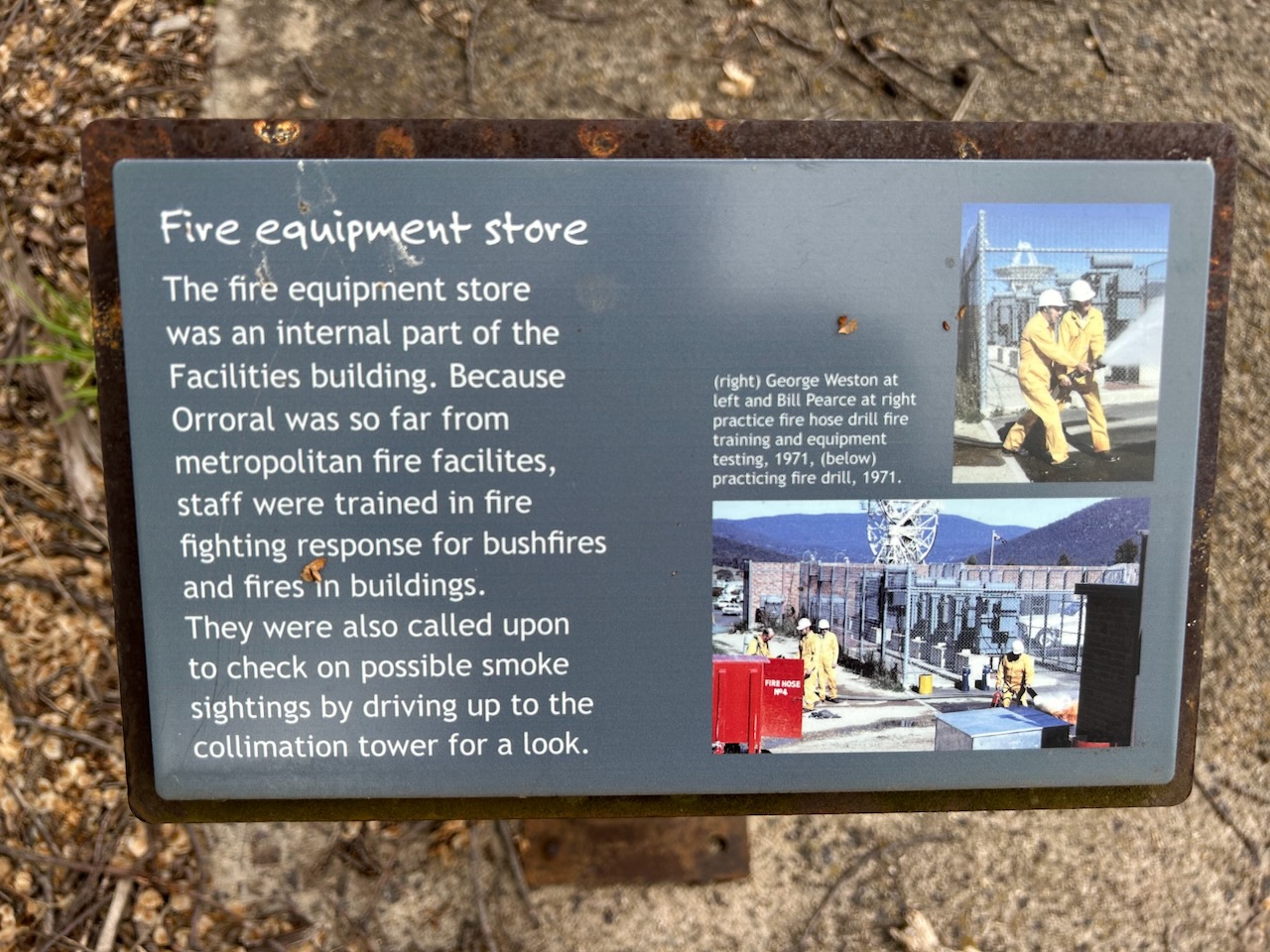

From 1965 to 1984, the Orroral Tracking Station operated 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, mainly tracking satellites in near-Earth orbit. The station closed when the control and monitoring of satellites was taken over by other satellites. In 1990, the buildings were removed from the site due to deterioration. All that remains now are some exotic trees and the footings of the buildings. You can undertake a self-guided walk around the site, which is what Marija and I did. There are several interpretive signs detailing the history of the site.

The Operations building was the ‘nerve centre’ of Orroral. The activities of the station, including administration and control of the antennas, occurred in the Operations building.

There was no commercial power supply to the Orroral Valley, so the tracking station had its own powerhouse.

The dish was built by NASA and installed in 1965. The antenna was erected by Collins Radio under contract to NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre. The diameter of the dish was 26 metres (85 feet), and it stood at 36.5 metres (120 feet). It weighed 400 tonnes.

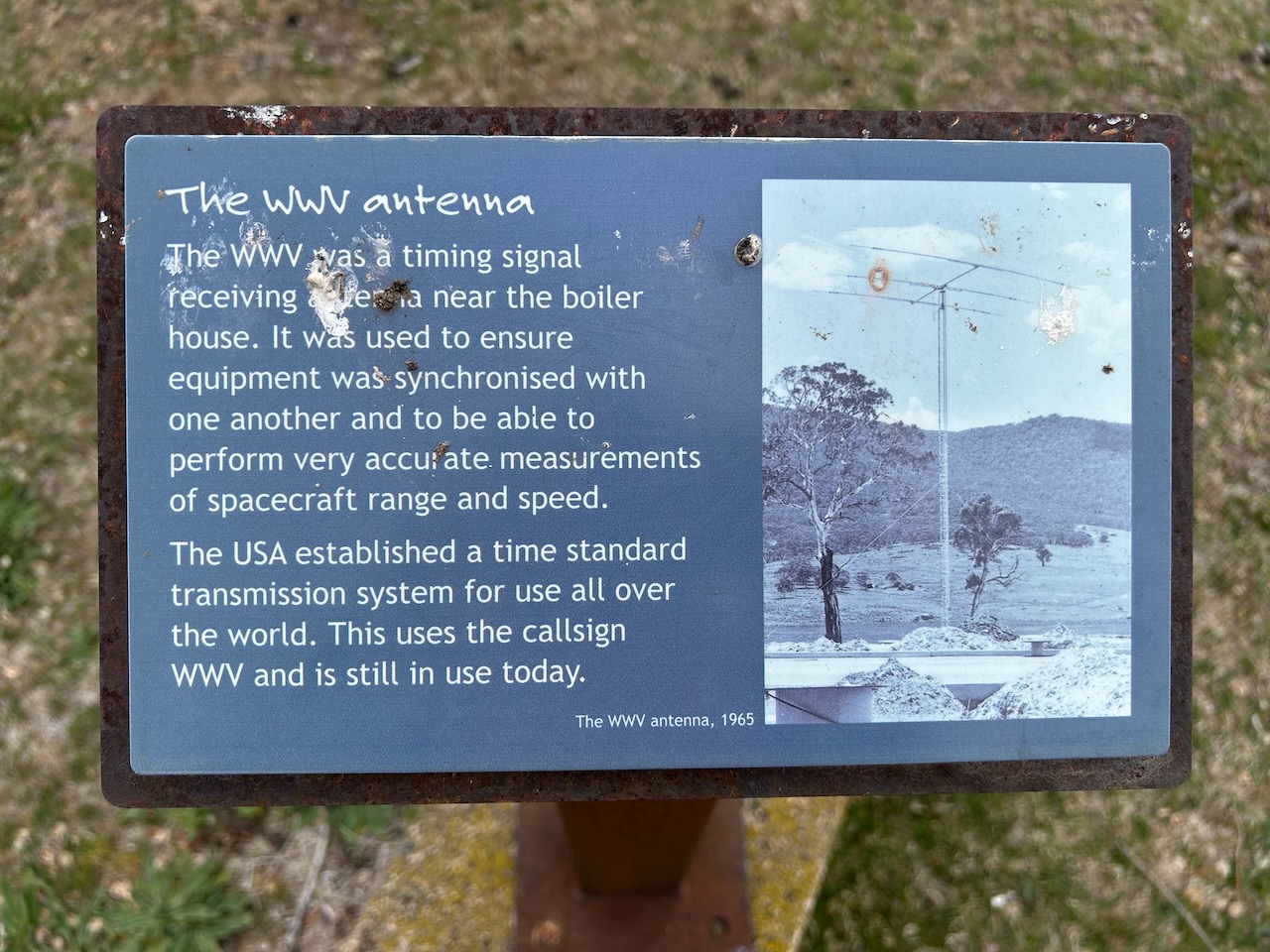

There were two Yagi antennas at Orroral. One was for satellite tracking, and the other was for receiving radio timing signals. The WWV antenna was a timing signal receiving antenna used to ensure that equipment was synchronised with one another.

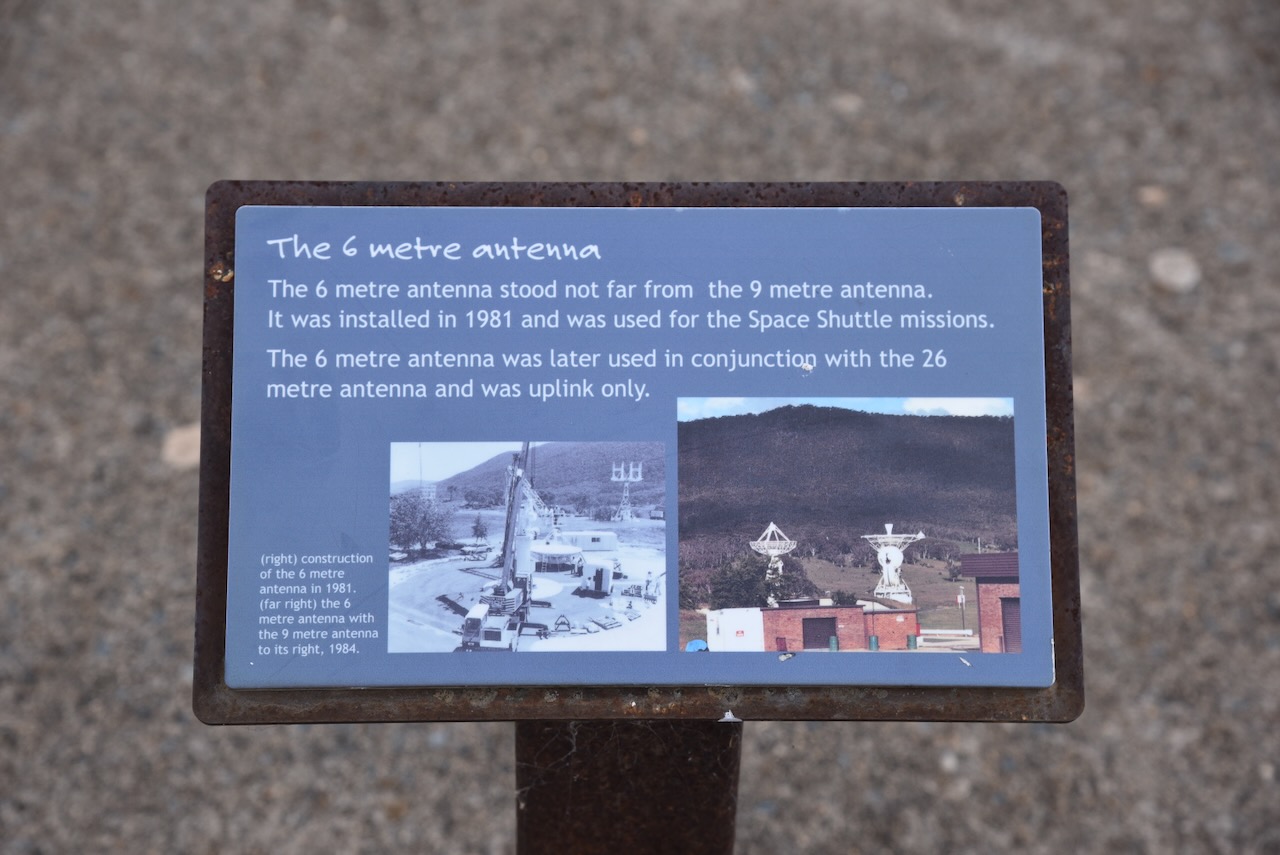

The 6 metre antenna stood not far from the 9 metre antenna. It was installed in 1981 and was used for the Space Shuttle missions.

This really is a fascinating place to wander around and imagine what it looked like when it was operational.

There is some Aboriginal art at the Orroral Tracking Station which shows the connection between the Ngunnawai Aboriginal people and the sky.

The Orroral Tracking Station had lush green lawns, exotic trees and shrubs. A gardening business owned by Fritz Rehwinkel and based in Queanbeyan was contracted to landscape the tracking station site.

There was a large mob of kangaroos on the site during our visit.

Marija and I then left the Orroro Valley and travelled south along Boboyan Road, admiring the spectacular Namadgi National Park.

Our next stop was the Hospital Hill lookout on Boboyan Road. There is a small parking area here off the road and a viewing platform with an interpretive sign giving details of the various summits that you can see from this point. The view across Gudgenby Valley towards the ACT/New South Wales border is magnificent. Apparently, Hospital Hill takes its name from the practice of accommodating calving, lambing or sick animals at this location. (Johnevans.id.au 2017)

Marija and I continued south along Boboyan Road through the Namadgi National Park.

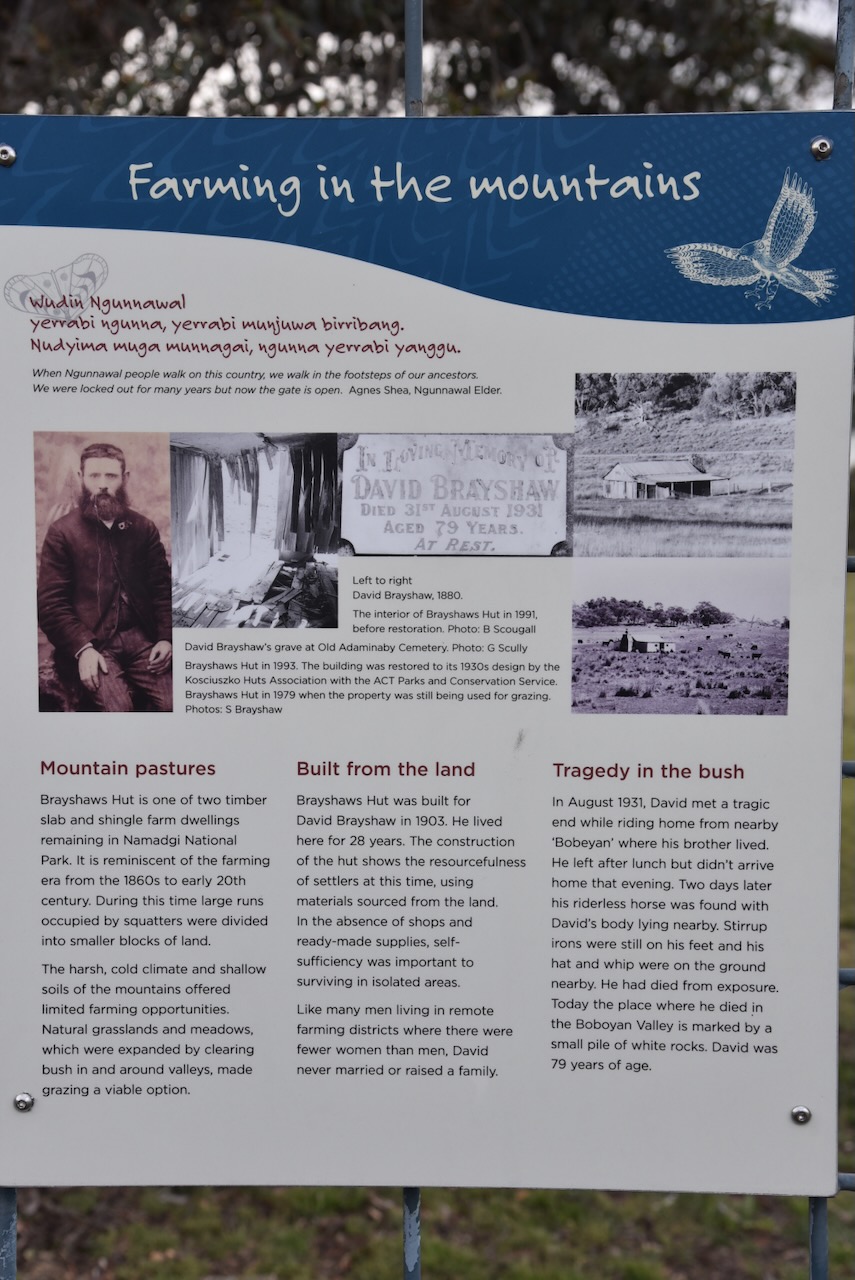

Our next stop was the historic Brayshaws Hut, which is also referred to as Brayshaws Homestead. The hut was built in 1903 by Edward Brayshaw for his brother David.

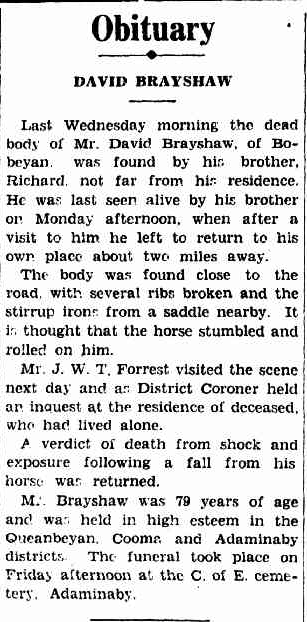

David Brayshaw was born on the 29th day of July 1852 at Bobeyan, New South Wales. He was one of 14 children to William Brayshaw (b. 1810. d. 1988) and Flora Crawford (b. 1821. d. 1891). In 1903, David moved into the hut after it was constructed by his brother. He lived there until his death on the 31st day of August 1931. His body was discovered by his brother Richard, not far from the hut. The District Coroner attended the scene the following day and held an inquest at the hut. A verdict of death from shock and exposure following a fall from his horse was returned. David is buried at the Adaminaby Cemetery. (Nla.gov.au 2026)

Above: Obituary of David Brayshaw, Queanbeyan Age, Tue 8 Sept 1931. Image c/o Trove

You can enter the hut, which has been restored.

Marija and I continued south along Bobeyan Road and stopped to have a look at the Adaminaby Racecourse. This little racecourse is really in the middle of nowhere, about 3.5 km east of the town of Adaminaby.

The present racecourse is not the original Adaminaby racecourse. This is due to the town moving for the Snowy Hydro Scheme and the creation of Lake Eucumbene. The old racecourse is now underwater. The present course is about 50 years old. More than 2,000 people gather for the annual Adaminaby Races, which date back to the 1860s. (Adaminabyraces.com.au 2025)

Above: article from the Manaro Mercury, Friday 10 April 1863. Image c/o Trove

We then drove the short distance to the town of Adaminaby.

The Adumindumee run was established in the 1840s. Adumindumee is believed to be a corruption of an Aboriginal word meaning either ‘camping or resting place’ or ‘place of springs.’ (Marshall 2022)

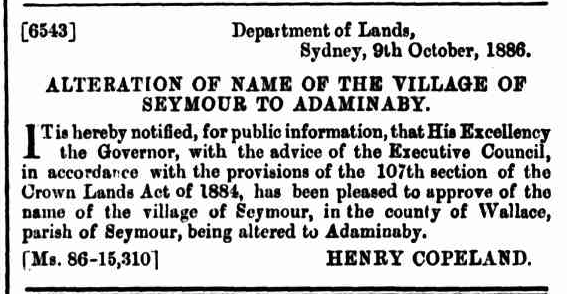

The town of Seymour was surveyed in 1861. On the 9th day of October 1886, it was renamed Adaminaby. This was due to avoiding confusion with the town of Seymour in Victoria. (Marshall 2022)

Above: reference to the name change in the NSW Govt Gazette, Sat 9 Oct 1886. Image c/o Trove

The town of Adaminaby was moved due to the construction of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electricity Scheme, which commenced in Adaminaby in 1949. (Wikipedia 2016)

Charlie McKeahnie from Adaminaby is believed to be the inspiration for the poem ‘The Man from Snowy River’ by Banjo Patterson. He is the grandson of Charles Duncan McKeahnie who I spoke about earlier in this post. (Wikipedia 2026)

The poet Barcroft Boake also wrote about McKeahnie’s ride in ‘On the Range.’ McKeahnie chases down a well-bred horse that had escaped with a mob of wild brumby horses. (Wikipedia 2026)

Charlie Lachlan McKeahnie was born in April 1868 at Queanbeyan, NSW. He married Sarah Anne Read in 1890. They had 2 children. McKeahnie died in a riding accident in 1895. (ancestry 2016)

We briefly had a look at the outside exhibits of the Snowy Scheme Museum at Adminaby. Unfortunately, the museum was closed as it was late in the afternoon. Marija and I agreed that we would have to come back to have a good look around Adaminaby and the district.

The Adaminaby district is well known for trout fishing. The town features a 10 metre tall Big Trout. It was built by a local artist, Andy Lomnici and was completed in 1973. It underwent a restoration in 2024 by Ryan Loughnane, a Sydney-based mural painter. (Visitnsw.com 2016)

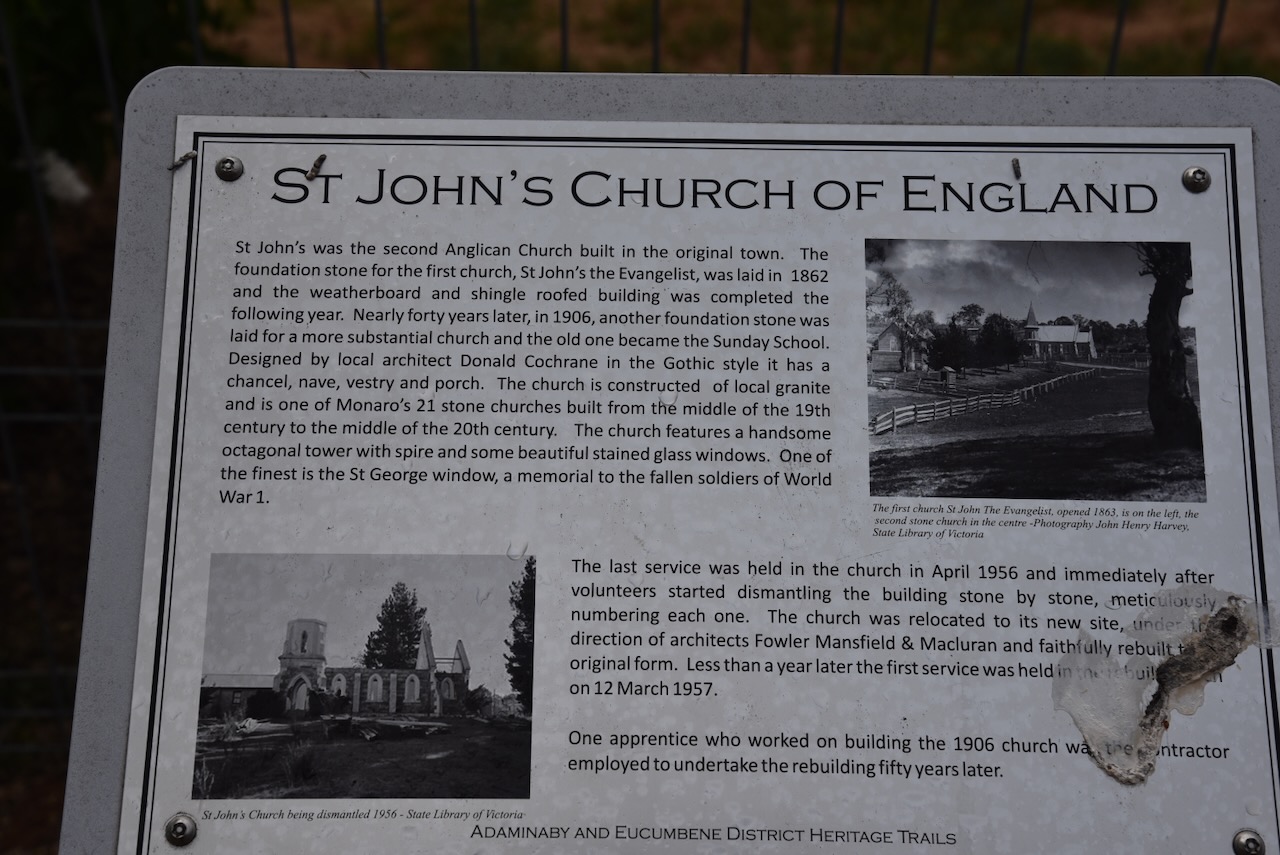

St John’s Church of England in Adaminaby was the second Anglican church built in the original town. The last service was held in the church in April 1956. Following this, a team of volunteers commenced dismantling the church stone by stone. The church was relocated to its new site and rebuilt. On the 12th day of March 1957, the first service was held in the newly built church.

Marija and I then drove southeast on Snowy Mountains Highway towards the town of Cooma. About 6 km west of Cooma is the Snowy Mountains Travellers Rest. The Inn was constructed in 1861 by Hugh Stewart. It housed bullock teams as they travelled from the Kiandra goldfields to Cooma to obtain supplies. (Visitnsw.com 2016)

We then drove a short distance out of town to the Kuma Nature Reserve VKFF-1954.

The reserve is about 184 hectares in size and was established in March 2003. It is an example of the natural temperate grassland of the Southern Tablelands and is recognised as a threatened ecological community under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. It was created to protect endangered and vulnerable reptile species and a remnant area of their natural habitat. Most of the surrounding countryside is used for cattle and sheep grazing. (NSW NPWS 2007) (NSW National Parks 2026)

The name Kuma is derived from an early spelling of Cooma, which was the Aboriginal name for the area. The reserve was purchased in 1997 following the drought that year. It was privately owned and had been used for grazing. (NSW NPWS 2007)

The Kuma Nature Reserve is home to three species of threatened grassland reptiles. The Grassland Earless Dragon is listed by the NSW and Commonwealth Governments as endangered. The Striped Legless Lizard and the Little Whip Snake are listed as vulnerable. (NSW NPWS 2007)

There was a ladder over the fence allowing access to the reserve. We set up just alongside the fenceline as we were cognisant of the endangered reptiles that lived in the reserve. We ran the Yaesu FT857, 40 watts, and the 20/40/80m linked dipole.

Marija worked the following stations on 40m SSB:-

- VK1AO

- VK2MET

- VK5NJ

- VK5LA

- VK5KAW

- KG5CIK

- VK3APJ

- ZL2BH

- VK2LTP

- VK2EIT

- VK2AIT

- VK2AIQ

- VK2AIX

- VK2AIZ

- VK2YAK

- VK4YAK

- VK5HS

I worked the following stations on 40m SSB-

- VK1AO

- VK2MET

- VK5NJ

- VK5LA

- VK5KAW

- KG5CIK

- VK3APJ

- ZL2BH

- VK2LTP

- VK2EIT

- VK2AIT

- VK2AIQ

- VK2AIX

- VK2AIZ

- VK2YAK

- VK4YAK

- VK5HS

- VK3AMO

- VK3MCA

- VK4SMA

- VK2HOO

- VK2MG

References.

- ACT Heritage Council, 2016, Background Information Orroral Valley Tracking Station

- ACT Memorial. (2024). Search. [online] Available at: http://www.memorial.act.gov.au/search/person/cunningham-andrew-twynam. [Accessed 15 Feb 2026]

- Adaminabyraces.com.au. (2025). Adaminaby Races – Saturday 22nd November 2025. [online] Available at: https://adaminabyraces.com.au/ [Accessed 16 Feb. 2026].

- ancestry (2016). Ancestry® | Genealogy, Family Trees & Family History Records. [online] Ancestry.com.au. Available at: https://www.ancestry.com.au/. [Accessed 15 Feb 2026]

- Johnevans.id.au. (2017). Local Names – Johnny Boy’s Walkabout Blog. [online] Available at: https://johnevans.id.au/other-resources/local-names/ [Accessed 16 Feb. 2026].

- Marshall, C. (2022). A complete guide to Adaminaby, NSW. [online] Australian Geographic. Available at: https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/news/2022/12/a-complete-guide-to-adaminaby-nsw/ [Accessed 16 Feb. 2026].

- Nla.gov.au. (2026). Making sure you’re not a bot! [online] Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/265200424?searchTerm=david%20brayshaw%20%2B%20fall%20from%20horse [Accessed 15 Feb. 2026].

- Nla.gov.au. (2026). Making sure you’re not a bot! [online] Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/271512542?searchTerm=orroral%20%2B%20bootes [Accessed 16 Feb. 2026].

- NSW National Parks. (2026). Kuma Nature Reserve. [online] Available at: https://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/visit-a-park/parks/kuma-nature-reserve [Accessed 16 Feb. 2026].

- Visitnsw.com. (2016). The Snowy Mountains Travellers Rest. [online] Available at: https://www.visitnsw.com/destinations/snowy-mountains/cooma-area/cooma/food-and-drink/the-snowy-mountains-travellers-rest [Accessed 16 Feb. 2026].

- Visitnsw.com. (2016). Big Trout. [online] Available at: https://www.visitnsw.com/destinations/snowy-mountains/cooma-area/adaminaby/attractions/big-trout [Accessed 17 Feb. 2026].

- Wikipedia Contributors (2026). Adaminaby. Wikipedia.